The Echo Park Dam and the Fight to Save Dinosaur

Essay written by Mike Lord, April 2011

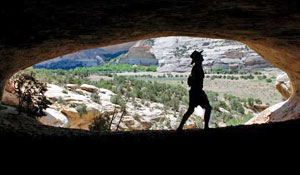

Echo Park is a special place. Located in the heart of Dinosaur National Monument in the northwest corner of Colorado,

it is a tranquil spot of immense sandstone cliffs just below the confluence of the Green and Yampa rivers. From below the towering 800 foot Steamboat rock, you can yell and hear your voice

echoed back to you many, many times from almost every direction. This unique effect led to the area's naming by John Wesley Powell, one of the river's first explorers.

I was lucky enough to first experience the effect when I was a teenager. As a Georgia native, I had never before floated though canyons quite like those of Dinosaur National Monument with

its massive sheer cliffs, bighorn sheep, and desert surroundings. One experiences a sense of awe and solitude there that cannot be found in many places in America. It left an impact on my family

and me. We returned to the Monument several times over the next few years, rafting on both the Green and Yampa rivers multiple times each. I so enjoyed the place that when it came time for a career

change, I applied for a job as a river guide with Adventure Bound River Expeditions, the very same outfit that had first exposed me to Dinosaur as a youngster. I now have the privilege of watching

others enjoy the grand beauty of the canyon and the entertainment provided by the echoes of Echo Park.

As a guide in the Monument, it is part of my job to tell people about the history of the place. There is this certain spot in Whirlpool canyon that I am particularly fond of and usually stop at

to prepare lunch for our guests. It has a nice rock overhang on the left side of the river that provides a place to relax and get out of the sun for a little while. This picturesque locale also happens

to be the exact spot where a dam was proposed in the 1950s. I have often sat there munching on a sandwich, talking to our guests about the proposed dam, struck by the fact that the rocks I am eating on

could very easily be hundreds of feet under water if not for the actions of the nascent environmental movement. Back in those days, the term environmentalist was not yet part of our modern lexicon. Back

then, they were simply conservationists.

The actions of the conservationists that joined together in order to protect Echo Park and Dinosaur National Monument (DNM), have had a lasting impact on the environmental movement in the US. Their

fight helped Americans realize the need to protect our wild spaces. It provided a jumpstart to the environmental movement and secured the protection of our National Park lands. Many of the organizations

that mobilized to fight the construction of the dam in Echo Park became household names and environmental leaders. These now familiar groups included organizations such as the Sierra Club and the Wilderness

Society, whose names are today synonymous with environmental activism.

The organizations involved in the campaign had no precedents to follow. There had never been a successful attempt to fight such a large

government development project. John Muir had tried and failed in a similar battle over Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. That heartbreaking loss had given developers the upper hand, but Echo

Park would change that. There were no laws for the conservationists to turn to. The Wilderness and Endangered Species Acts, both commonly used today by modern environmentalists to challenge development

projects, did not yet exist. Their creation would come as a result of the actions taken to fight the Echo Park dam.

With no legal options or precedents to follow, the conservationists had to be creative in how they challenged the proposed dam. Their only real choice was to take the fight into the political arena. The

story of their successful struggle to save Dinosaur is an important chapter in the modern environmental movement and one that is close to my own heart. There are important lessons to be learned from their

struggle and examples to be followed for anyone interested in taking a stand in the name of conservation.

Return to Top

Motivations for building in Echo Park

The main proponent and creator of the plan to build a dam in Echo Park, and the major opposition in the struggle to save Dinosaur, was the Bureau of Reclamation (BR). The BR is part of the Department of

the Interior and was formed in 1902. It was a keystone of the Progressive Era conservation movement. Conservation during this era was based on the idea of protecting resources for future use. Lands were not

protected for beauty or enjoyment by future generations, but saved in order to manage the natural resources of the nation.

During this time, the BR was busily building dams, canals and irrigation and power facilities all over the West. They sought to put efficient use to the West's water resources. The BR evolved into a major

force in the region. Their power and influence was extensive and they had offices in many of the West's major cities, including Denver, Billings and Salt Lake City. Throughout the early part of the 20th century,

the BR developed a reputation for harnessing western rivers and stimulating economic growth. They were a highly trained professional organization made up of geologists, hydrologists and engineers. The battle

to save DNM was just the beginning of what would be a very icy relationship between environmentalists and the BR that would last for decades.

The dam at Echo Park was first proposed in the 1940s as part of the Colorado River Storage Project (CRSP). The CRSP called for a series of dams to be built along the Colorado River system in Wyoming, Colorado,

New Mexico and Utah. The Echo Park dam was a major component of the overall project and was often referred to by proponents as the "piston in the engine" of the CRSP. The plan also called for major dams

in Glen Canyon and Flaming Gorge. The CRSP was designed to provide electricity for rural development and growing cities, as well as water storage and river control. Overtime, the project became a symbol of growth

and prosperity for a West that was still rather wild and undeveloped.

The region was growing quickly in the post war years and dam building to regulate water and produce power offered benefits to ranchers eager to irrigate dry lands, farmers who belonged to rural electrification

cooperatives and businessmen eager to expand and build. The need to regulate water between the upper and lower Colorado River basins was another major motivation for the CRSP. The Colorado River Compact of 1922

ensured that all seven states that the river flows thru got a share of the water. The compact required that half of the river's water be sent downstream to the lower basin. This was perhaps the single greatest

motivation for the CRSP and the dam at Echo Park. The upper basin wanted to make sure they got their fair share of the water. They wanted to ensure that the upper basin had the means to control what went downstream

and retain enough water to meet their growing needs, and the CRSP was designed to do just that. One of the upper basin's greatest fears was to awaken and find that all their precious water had needlessly flowed to

California.

There were several reasons for Echo Park's selection as the lynchpin of the CRSP. Its high cliffs and strong rock made it a sound engineering choice and its depth and narrowness promised to limit surface area,

and thus, limit evaporation. The location of the dam in Echo Park also allowed for the damming of two major rivers within a single reservoir. Both the Yampa and Green rivers would be controlled and backed up by the dam.

This was one of the major reasons proponents of the dam would be so against the proposal of alternative sites throughout the conflict. Echo Park's surrounding areas were expected to grow over the coming decades, and

because of this, the market and revenue created by the dam was expected to help pay for the other reclamation projects in the CRSP. It was expected to spark development in the region just as the transcontinental railroad

had for the West in general during the previous century. The benefits of the dam seemed numerous, but the consequences of the project were great as well.

Return to Top

The need to take a stand

By the time the conservationists won their battle against the proposed dam at Echo Park, over 78 organizations had joined the fight. These various organizations brought with them a myriad of interests. There were

many reasons to build the dam, and many reasons to fight the project, but one of the best reasons to fight stands paramount to the rest. The overall goal that united the many different organizations was the protection

of the National Park System (NPS). The Echo Park dam threatened the very idea of the NPS. The dam at Hetch Hetchy had set a dangerous precedent and demonstrated that NPS lands were vulnerable to development. Conservationists

felt that a stand must be taken against the proposed destruction of yet another scenic river system located inside the NPS. They believed that federally protected lands should be off-limits for development. The fight against

the Echo park dam was vital to upholding the principles on which the NPS was founded. It was felt that if a stand was not taken against this project, it could risk opening up all NPS lands to development.

This notion of protecting the National Parks was the overarching motivation behind the fight, but it was not the only factor. As those involved in the fight became more familiar with the little known DNM, it became

obvious to many that the area was worth protecting simply because of its beauty and solitude. This unique place had been protected by the NPS for a reason and it was worth preserving for its intrinsic value alone. There

were also those who believed that such wild places were necessary for both recreation and the rejuvenation of the human spirit, something often needed in the hectic realm of urban life. Whatever the various personal

motivations might have been, the coalition that formed to protect Echo Park remained focused throughout the fight on the single goal of protecting the NPS.

Return to Top

Setting the stage

At the time of the controversy, Dinosaur was a little known and remote NPS holding. The lack of attention and notoriety was one of several factors that helped set the stage for the controversy. The monument's name itself

is a bit misleading. In July of 1938, President Roosevelt signed the proclamation that set aside the Green and Yampa canyons. For convenience sake, the newly protected area was grafted onto the already existing Dinosaur

National Monument, established by Woodrow Wilson in 1915 to protect the dinosaur quarry near Jensen, Utah. The new addition of land expanded the tiny monument into one of the largest NPS holdings at more than 360 square miles,

about 200,000 acres. The name of the park helped in its early identity crisis. It was not a park primarily set aside to protect dinosaur bones, as the name would suggest. The lands were set aside largely to protect the canyons

and the rivers that flowed through them.

Proponents of the dam often used its name to mislead the public. They repeatedly stated that the dam would not affect the dinosaur bones, which due to its name, many people believed to

be the main reason for the areas preservation. The dinosaur bone issue would be a constant distraction throughout the conflict. The monument also suffered from a lack of funding and remained undeveloped. This too led to it's

public anonymity. National Parks as a whole saw record numbers of visitors in the postwar period. Americans took to the roads for family vacations and the National Parks were immensely popular destinations. During this time,

however, DNM received few visitors and remained unknown. This lack of attention led developers of the CRSP to assume that there wouldn't be much a fight to protect it.

The original charter for the park signed by Roosevelt also helped to set the stage. It included wording that left open the possibility for future dam projects. Even as far back as 1938, developers had their eye on the water

in the two rivers that flowed thru DNM. At that time, however, possible plans had hinted at a dam upstream from Echo Park in Brown's Park. Because of this original wording, the Bureau of Reclamation had no reason to believe

that the NPS, or anyone else, would object to a dam in the monument.

Another major factor in the controversy was the explosive economic growth in the region during the post-WWII era. Utah, in its search of new sources of power and water, created the Water and Power Board, which quickly became

an ardent supporter of the CRSP. Articles were published in all the local newspapers explaining the need for the CRSP. In just a short amount of time, a large majority of the local population got on board with the CRSP. Public

backing meant the backing of the local politicians, and thus, Senators from the region took up the CRSP as a their major political cause. The upper and lower basin states began the long process of working out the details of each

state's share of the Colorado River’s water, which culminated in the Upper Basin Compact of 1948. With the passage of this second major document controlling the Colorado River, the way was paved for the states and the BR to begin

the process to make the many projects of the CRSP a reality. The BR's budget skyrocketed in the postwar era which gave them a huge advantage over lesser agencies like the NPS. The local Senators and the BR formed an influential

and united political front in support of the CRSP and the dam at Echo Park.

Despite this political unity and local support, there was growing opposition to the CRSP for many reasons. The conservation movement in America was growing as urbanites began to explore the more wild regions of the country.

As I mentioned before, visitation to the country's national parks was setting new records every year. Many saw the NPS as an almost sacred element of the country and worthy of protection. Hecth Hetchy had struck a nerve with

many conservationists and they were not about to let the same thing happen to another part of the NPS.

So with these major factors in mind, the remoteness of the park and lack of public recognition of what it protected, the local and political support for the CRSP and the proposed dam at Echo Park, and the rising influence of

the conservation movement in the US and their desire to once and for all make all NPS land off limits to development, the stage was set for a major battle. The ensuing struggle would last for over 6 years, and with the victory

of the conservationists, would secure the protection of the NPS and the place of the growing environmental movement in the debate over future development and the need for conservation.

Return to Top

The battle begins and the conservationists form a plan

The first stage of the battle took place within the Department of the Interior in 1949. Both the BR and the NPS are a part of the department, and it was the Secretary of the Interior that had the authority to recommend, or

make changes to the CRSP before it was presented to Congress for approval. In 1949, the NPS was headed by Newton Drury, the BR by Michael Straus, and the Secretary of the Interior was Oscar Chapman. Drury was against the

construction of the dam in Echo Park, Straus was for it and Chapman was caught in the middle. Truman was President and he wished to follow the Democratic tradition started under FDR and the New Deal that provided rural

communities with dams and power. He also wanted to ensure that the Republicans did not steal the 'water and power' vote that was becoming increasing power in the West. Truman even went as far as to support the development

of valley authorities in the West similar to the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which turned out to be a rather impractical idea. So Chapman was under a lot of pressure from the federal, state and local levels to approve

the project. But at the same time, he also faced increasing protest from the NPS and various conservation groups against aspects of the CRSP.

With all these various interests in mind, in June of 1950, Chapman held a hearing to debate the issue. Speakers from both sides attended the meeting, but due to the rather hasty manner in which the hearing was organized,

many conservation groups could not send representatives. A few did manage to attend, including the Sierra Club, Isaak Walton League and Wilderness Society. The majority of the meeting, however, was devoted to the pro-dam side.

The CRSP was projected to cost $1.5 billion in its first phase alone. Some of the debate at the hearing focused on this rather large price tag. Pork barrel claims were made and Republicans, with the exception of those

from the West, had grown increasing critical of large spending projects. While some of the testimony focused on spending issues, the majority of it was focused on DNM itself. Unfortunately, only two of the anti-dam people

present had ever been to the Monument. Both Fredrick Law Olmstead Jr. and Dr. Frank Setzler had floated the river, and they made arguments for its beauty, comparing it to the Grand Canyon for its geological and scientific

significance. Drury testified at the hearing and argued that the BR was exaggerating the need for dams in the region and that they had not seriously considered sites that were outside NPS protected areas. Conservationists

also argued that the dam in DNM would set a harmful precedent for the NPS. They tried to appeal to Chapman's sense of stewardship reminding him that as Secretary of the Interior he had a duty to uphold the National Park

charter to protect scenic landscapes for future generations. The conservationists also pointed to the growing popularity of the National Parks and that appreciation for nature could not be measured in dollars and cents.

The proponents of the dam countered by reminding Chapman of the interagency planning for the CSRP, which the NPS had been a part of. Strauss even presented a document that Drury had signed in 1944 that stated the NPS would

not oppose a dam at Echo Park, if and when Congress approved such a project. Proponents also emphasized the fact that the canyons would be flooded, ridding them of the dangerous rapids and actually opening them up to more visitors.

They argued that a nice placid reservoir was surely preferable to people wishing to see the canyons. Whitewater as a recreation was not yet popular and was viewed as overly dangerous by many. They also, of course, argued that the

dams were needed for water storage and power and that the DNM dams, at the time they were proposing dams at both Echo Park and downstream at Split Mountain, were predicted to have low evaporation rates compared to other possible

reservoir sites. This claim would later become a major focus of the controversy. The entire congressional delegation from Utah showed up and flexed their political muscles. All in all, the proponents greatly outnumbered the

conservationists. The pro-dam side had the upper hand in all aspects of the hearing.

Chapman took a while, but eventually approved the dams in June of 1951. He cited both the low evaporation rates of the DNM dams and the fact that they had been contemplated since the park's expansion in 1938 as major

influences for his decision. He also stated that no dangerous precedent would be set for the NPS because Dinosaur was just a National Monument and not a National Park. Cold War escalation also played a role in his decision,

though it was not stated at the time. Truman had just ordered the testing and development of the hydrogen bomb in Utah and Nevada. The program needed a reliable source of power, and hydroelectricity from the Echo park dam

would provide it. This could have been the single largest motivation for Chapman's approval of the project, but he had to cite other reasons due to the sensitivity of the H-bomb project. Chapman's approval alone, however,

was not enough. The CRSP still had to pass the Congressional budget committee. June of 1951 also saw the start of the Korean War, which put increased pressure on the government to watch its money. In this atmosphere, the

CRSP found it hard to find support from members of Congress outside the West.

After Chapman's decision, Harper's Magazine columnist, Bernard DeVoto, became an ardent opponent of the Echo Park dam. DeVoto was a native of Utah, but had left to pursue a career as a writer in Cambridge, MA, and had even

taught briefly at Harvard. By 1951, he was a well-known writer and historian and had written several histories of the West. He had often written against Western development and was pro-nature to the dismay of many in his home

state. He wrote several articles critical of the CRSP. His article "Shall We Let Them Ruin Our National Parks?" appeared in the Saturday Evening Post and helped to fully launch the public battle to save Dinosaur. Echo Park had

been brought to the attention of several of the conservation leagues, but the public at large was still ignorant of the issue. DeVoto's article helped to change that. Reader's Digest reprinted the article and helped to expose

an even wider audience to the issue. DeVoto recognized that the public at large had the ability to pressure their local representatives to save Dinosaur, and it was for that reason he wrote out against the project. His article

also angered the locals. They viewed the conservationists as outside elitists who had never visited the park, yet wanted the locals to preserve it at their own economic expense. The conservationists and DeVoto were demonized

in the local press and portrayed as out of touch with reality and simply branded as 'nature lovers'.

Drury's disappointment with Chapman's decision was obvious. He formed close ties with DeVoto and was accused by Straus of supplying information for his articles against the Echo Park dam. Drury denied the accusations, but

continued to speak out in the NPS against both Chapman and Straus. Chapman realized that the cooperation of the director of the NPS would be vital during the construction phase of the dam in Echo Park and he was not going to

get such cooperation from Drury. He knew the situation had to change and offered Drury a lesser position in the Department of Interior. Drury realized he was being forced out of the NPS director job, and rather than take the

lesser position, he left the federal government and became the head of all CA state parks, a prestigious conservation post at the time. Conservationists, including DeVoto, demanded an explanation for Drury's departure. Chapman

refused to give a straight answer, but many people correctly concluded that it was because of his opposition to the Echo Park dam.

The combination of Drury's removal and DeVoto's Post article helped to bring lots of attention to the campaign to save Dinosaur and galvanized the opposition. Conservationists became determined to fight the battle in Congress.

The groups that came together to fight the proposed dam at Echo Park were all united in the desire to protect the NPS from development, but they needed a united plan of action. Western states were very powerful in the Senate, and

they were, of course, all pro-dam, so the conservationists decided they needed to take their fight to the House. They needed to make a strong case for protecting DNM and the NPS as a whole, as well as prove that the upper basin

could manage its water supply without destroying NPS land.

The conservationist coalition was by this time led by Howard Zahniser of the Wilderness Society, Ira Gabrielson of the Emergency Committee of Natural Resources, Fred Packard

and Sigurd Olson of the National Parks Association and David Brower of the Sierra Club. Together they came up with a three part strategy: promote and make known to the public the scenic beauties of Echo Park and Dinosaur National

Monument, forge partnerships between conservationists and other groups that opposed parts or all of the CRSP, and fight the BR on their own turf by making technical arguments for other sites that would spare DNM. With this newly

adopted strategy in hand, the conservationists were ready to begin the real battle to save Dinosaur.

Return to Top

Alternative Sites

Attacking the proposed Echo Park dam on technical issues was perhaps the most risky of the three-part strategy adopted by the conservationist coalition. If they failed to make a proper argument it could discredit the entire

campaign. The first technical issue they went after was the site itself. Alternative proposals had been made throughout the early stages of the controversy, but all had been rejected and had simply helped to solidify the BR's

support for the Echo Park site. The conservationists were eager to portray themselves as in favor of the CRSP as a whole, just not any part of it that threatened NPS land. For that reason it was essential for them to propose

alternative sites.

The conservationists found the expert support they needed in order to credibly propose alternative sites in the form of General U.S. Grant III, grandson of the famous Civil War general and President. Grant was a former staff

member of the Army Corps of Engineers and had worked on several dam projects during his 40-year career. That experience allowed him to take a close and skeptical look at the CRSP. His skepticism was aided by the fact that the

Army Corps and the Bureau of Reclamation often competed for funding and projects. This had led to a rivalry of sorts between the two departments, which had provided Grant with practice evaluating BR projects in the West.

Grant studied the CRSP and came up with several alternative sites that would spare DNM. Among the alternative sites he proposed were dams at Cross Mountain on the Yampa, one near Moab on the Colorado and ones on the Green

River in Desolation and Grey Canyons. He did not propose a higher dam at Glen Canyon, which would later become the major alternative supported by conservationists and a very controversial decision in its own right. Grant also

challenged the BR's claim that Echo Park was necessary because of low evaporation rates. Perhaps most importantly, Grant challenged the BR's projected costs for the CRSP. He argued that they had projected too high a cost for

hydroelectricity. He stated that if they really charged as much as they were predicting, it would not be competitive with other forms of electricity, and if they charged less then the high prices they proposed, they would not

pay off the dam in the allocated 50 years. The Army Corps joined the debate and also claimed that project costs raised some serious doubts over the CRSP.

In light of the new arguments from Grant and the Army Corps, Chapman began to seriously question his earlier decision to approve the CRSP. Due in part to the budget demands of the Korean War, in 1951, Congress refused to fund

water projects that were not already underway. In November of 1951, during a speech to the Audubon Society, Chapman announced the formation of a task force to look into alternative sites for the Echo Park dam. Grant's criticisms

had hit their mark and Chapman was unwilling to endorse the CRSP and send it before Congress while opposition remained from the Army Corps. Local Senators continued to propose the CRSP before Congress, but it stood no chance

without the support of the Department of the Interior. In December 1952, Chapman officially withdrew his early approval of the Echo Park dam and recommended that the Split Mountain dam be deleted from the CRSP. The Echo Park dam

was officially shelved and awaited decision by the next administration. This delay provided the conservationists with the time they needed to continue to rally their forces.

The Eisenhower administration brought the Republicans to power for the first time since Hoover. Overall, they had a more pro-business approach to resource management than the Democrats that had preceded them. Eisenhower

appointed Douglas McKay as the Secretary of Interior, replacing Chapman. Business interests rejoiced at McKay's appointment. It was assumed he would be very pro-business. Though conservationists were at first weary of the

new Secretary, some of his early decisions to protect the National Parks gave them a glimmer of hope. Eisenhower was anti-big water projects and valley authorities, such as the TVA, a Democratic institution, which added to

the conservationists' hope that the new administration would make a decision on Echo Park in their favor. McKay announced a "no new start" policy for large water projects and froze the BR's budget for FY1954. The

new administration was more interested in supporting private power industry growth than supporting public projects. The CRSP's huge budget, $1.5 billion up front followed by another $3 billion to complete the project, also

gave Eisenhower cause for concern. The NPS was still against the proposed Echo Park dam, and Director Conrad Wirth made certain that McKay new about Chapman's reversal based on cost concerns. At the time, it was looking more

and more unlikely that the new administration would approve the costly CRSP.

Return to Top

The publicity campaign - part 1

During the early stages of the controversy, Dinosaur remained unknown to most Americans. While the defensive strategy worked for some audiences, it was decided by the conservationists that a more positive approach was also

needed. It became apparent that appealing to conservationists and scientists alone would not be enough. They needed to get the public at large involved in the effort to save DNM. If the battle was ultimately to be decided in

the halls of Congress, then the best way to convince the Representatives was to convince their constituents. The movement needed to appeal to the growing sect of Americans that were searching for outdoor activity and adventure.

They needed to find a way to attract tourists, outdoorsmen, recreationalists and conservationists to their cause. The best way to go about doing this was to launch a public campaign that showed off the beauty and uniqueness of

DNM and exposed the public to its wonders. The unknown Monument needed publicity, not just in the form of articles like DeVoto's, but it needed photos, movies, exposure in popular media and a general publicity campaign that

highlighted the wonders of DNM and sent the message that they were in grave danger. Hopefully, by doing so, they could attract the support they needed in order to prevent the dam at Echo Park.

One of the best ways to experience the area is from the river and as the campaign to save Dinosaur seriously got underway, the conservationists tried to expose people to this fact. One of the many arguments used by supporters

of the dam was that the rivers were overly dangerous and accessible only to a select few foolhardy rivermen. The availability of cheap army surplus rubber rafts left over from WWII revolutionized whitewater river-running. During

this era, more and more people were able to see the wonders of the Green and Yampa canyons from the river, thanks to the efforts of dedicated river guides and the conservationists who frequently booked trips for both supporters

and opponents of the dam project. It was hoped that once they experienced a float thru scenic Yampa and Lodore canyons they would be motivated to save them. It was a tactic that had great success.

At the start of the campaign very few people were running the canyons of DNM. The only person that offered guided trips was a local businessmen and river enthusiast named Bus Hatch. Bus and his brothers had been exploring the

canyons on the Colorado River for decades and began to offer the first commercial trips thru DNM in 1932, but few people made the trip. Less than 100 people had traveled down the canyons until the 1950s. Bus was hired to take

Stephen Bradley and his friends and family down the Green and Yampa rivers in 1951. Bradley was enthralled by what he saw and began to rally for the park's protection. Stephen told his father, Harold, about the trip and he wanted

to see it for himself. Harold was active in the Sierra Club, as was his father who had known John Muir and witnessed firsthand the struggle to save Hetch Hetchy. In 1952, the same summer that Bus took NPS director Wirth down the

river, which helped to change his mind on the Echo Park dam, the Bradley clan made another trip down the Yampa. Harold took his home movie camera with him and documented the trip. Over the course of his float down the Yampa,

Harold fell in love with the park and vowed to do everything he could to help save it. His home movies would prove vital in his effort to save DNM. Upon returning to Berkeley, CA, he showed the movies to anyone that would watch

and began what he called a one-man campaign to save DNM. The movie highlighted both the beauty of the region and the thrill and fun of the new sport of river running. Bradley's films generated a lot of interest in the Sierra Club

and other conservation organizations in the area. They were so popular that he had to make copies in order to accommodate all the loan requests he received from interested groups.

Up until Bradley started to show his movies, support in the Sierra Club for the fight against the Echo Park dam had come mostly from its leadership and was rather formal in nature. As the club's name implies, most members were

solely concerned with the nearby Sierra Mountains. Bradley's movies offered them a glimpse of a new kind of wilderness. It showed them a land of colorful rocks, rushing rivers and winding canyons, a big change from the alpine

wilderness they were accustomed to. David Brower had recently been appointed the Club's new executive director. He too was enamored with the images he saw in Bradley's movies. The growing enthusiasm for the area among members of

the Sierra Club eventually led to the idea of Club river trips through the canyons.

During the summer of 1953, a total of 500 people floated the rivers of DNM. Over 200 of those were Sierra Club members who went with Bus Hatch, which provided a boom for his still rather small river business. All this traffic

on the river not only helped expose lots of people to the beauty of the place, but it also helped to counter the claims that the rivers were too dangerous for the average tourist. For the most part, the Sierra Club members fell

in love with the rivers of DNM, and with their support, Bradley urged that protecting Dinosaur and Echo Park be the Club's priority. As part of the Club's effort, they produced a film from footage gathered during their river trips.

They called it "Wilderness River Trail" and promoted it around the country. The film garnered lots of national attention and helped to further solidify the Sierra Clubs role in the fight.

The Sierra Club's executive director, David Brower, was one of the many Club members that participated in the river trips of 1953. Just as Bradley had done before him, Brower fell in love with the rivers and fully threw himself

into the campaign to protect them. He would become known as a central figure in the fight and played a vital role in its outcome. Brower had a great knack for bringing the controversy to the people. He also had an aggressive style

that prompted him to ask the tough questions and go after the project on several technical issues. He was a bit of a maverick in the conservation movement and stood out among the other coalition leaders. His energy and aggressive

style were instrumental in propelling the Echo Park debate into high gear and he made the Sierra Club a major force in the coalition. During the two years that followed his first trip down the rivers in 1953, Brower made the

controversy a personal obsession as well as the Sierra Club's.

The Isaak Walton League was another major player in the campaign and helped early on to bring attention and another perspective to the debate. They were interested in conservation for another reason; fishing. The Isaak Walton

League was a sportsman club and they were concerned that the dams in DNM would destroy some of their favorite fishing spots along the Green and Yampa rivers. At the time, they had more power and influence than the Sierra Club.

The League was led by Joe Penfold and William Voigt, Jr. Penfold had lots of local connections and was widely trusted. He was not as combative and controversial as either DeVoto or Brower, but every bit as committed to protecting

DNM. He argued that there was no need for a dam at Echo Park in order to fulfill the larger goals of the CRSP and helped to spread the word about Echo Park to outdoor sportsman around the country.

Return to Top

Evaporation rates

Brower and DeVoto believed that more should be done than simply laud the parks natural beauties and admonish the dangers the project posed for the NPS at large. They began to look deeper into the technicalities of the CRSP

and picked apart every aspect of it. Other group leaders were hesitant about this tactic. They thought by doing so they risked alienating other groups, because there were many groups in the coalition that were supportive of the

CRSP as a whole, but just not in favor of the Echo Park dam. Opponents of Brower and DeVoto's new tactic also thought that to challenge the entire CRSP was beyond their technical expertise and risked labeling conservationists

as unrealistic dreamers. It was a tactic that they believed was practically and politically unsound. After over a year of inaction on the issue by the Eisenhower administration, McKay gave his approval for the Echo Park dam.

He sited evaporation rates as his main reason. This gave DeVoto and Brower the issue they were looking for. They decided to make evaporation rates the central technical issue to attack the Echo Park dam on because McKay had

made it his justification for approval.

Following Mckay's approval of the Echo Park dam and the CRSP, the issue moved once again to Congress. The CRSP was still heavily supported in the Senate, so the conservationists' best chance was to fight it in the House,

where many of the groups held sway with Eastern House members. The House subcommittee on Irrigation and Reclamation held hearings in January of 1954. The hearings quickly became a battleground as both sides of the Echo Park

debate presented their arguments. Conservationists stressed their main concern of opening the NPS to development and thus setting a dangerous precedent. They made sure to reiterate that they were not against the CRSP as a whole,

just any part that infringed on protected NPS lands. The Bradley brothers presented films and photos of their Sierra Club trips through the canyons and argued for the Monument's recreational benefits. They also noted that the

whitewater was not as dangerous as people were being led to believe. Penfold admitted that access to the park was limited, but argued for increased spending on roads and access points regardless of the dam project.

Brower then delivered some of the most memorable testimony of the hearing by attacking the evaporation rate figures. His appearance before the subcommittee has taken on an almost legendary status in the annuls of the American

environmental movement. Brower found a mistake in the evaporation figures that the BR presented to the subcommittee. It was a simple calculation error that grossly affected the figures. A similar mistake had been found by Grant

years before, yet the BR had never bothered to fix it. Brower used the mistake to attack the evaporation rates and found other errors that cast further doubt on the BR's figures.

Brower's appearance before the subcommittee was only the beginning of the evaporation debate. It went on for months and became closely associated with his role in the campaign. Brower enlisted the help of Ric Bradley, son of

Harold Bradley, and a physics professor at Cornell University. Bradley set about the evaporation issue in a very methodical and scientific manner. Through his own investigation of the BR's methods, and by contacting scientists

in the field, he learned that evaporation rates of any sort were nothing more than an educated guess. The more he learned about the process by which the BR had arrived at their figures, the more ridiculous he found it to be that

their major argument for Echo Park was based on evaporation. He concluded that estimates for evaporation rates were subject to 25% error, and thus their use as justification for the controversial dam was completely unfounded.

He admitted that the Bureau engineers had done as good a job as anyone could in determining evaporation rates and that they had in no way intentionally misled. It was simply that science did not provide the necessary tools to

make accurate predictions. Too little was known about the many factors that affected evaporation for anyone to make an accurate guess of what they might be for Echo Park. Bradley and Brower argued that the case for Echo Park

should not be based on evaporation rates because they simply were not reliable.

Throughout the debate on evaporation rates, Brower had proposed a higher dam at Glen Canyon as a solution to the problem. The higher dam would negate the need to build a dam at Echo Park. The BR had argued against this

alternative based on their projected evaporation rates. In April of 1954, all of Brower and Bradley's hard work paid off. The BR admitted that they had made mistakes while comparing the evaporation rates of a low Glen Canyon

and Echo Park reservoir combination compared to a single larger reservoir at Glen Canyon. The new estimates showed that the rates of the two configurations were virtually the same. This blew the argument over evaporation rates

out of the water and Brower quickly released a press statement. The new findings were reported to Congress and a higher dam at Glen Canyon became a viable option and major part of the controversy. Brower's and Bradley's gamble

to attack the CRSP on technical issues turned out to be a good one. Their success gave the conservation groups a boost in confidence. As a result, they began to believe that they might be able to win after all and this helped to

solidify the coalition's resolve to defeat the project.

Return to Top

The political debate

It is important to note that the debate over the Echo Park dam and the CRSP had developed in Congress over time from simply a conservation matter to a political one. Many Eastern and Midwestern states opposed the high costs

of the project, while Western states still argued for it's necessity. Interests of all sorts began to inject their own agendas into the controversy. Much of the debate turned to the overall cost of the CRSP and its value to the

nation as a whole. Proponents argued that the project would allow industry to spread throughout the country and provide new farming areas that would ensure plenty of food for the growing nation, both of which would be beneficial

to the nation as a whole. Eastern industrial areas and Midwestern farmers were against such a spread. They viewed the prospect of Western entrance into their markets as a direct threat. They allied with the conservationists against

the CRSP as a way to protect their own economic security. Private power companies, however, supported the CRSP. They stood to save a lot of money if the government footed the bill for the dam and infrastructure construction for the

power that they could then buy and sell in the local market. Tensions over water rights also began to develop between the upper and lower Colorado River basins. California was concerned that the CRSP would limit the water that

flowed downstream, and thus came out against the project.

Eisenhower eventually agreed to the CRSP for what many would view as political reasons. He had initially come out against large water projects, but due to his need for political support in the West, he made the decision to

support the project. Eisenhower had been criticized in the West for his opposition to large water projects and wanted to prove to voters there that he was not against all projects. He also needed the support of his close ally,

Senator Arthur Watkins of Utah, in other political matters, and in order to do so needed to support the CRSP, which was very important to Watkins and his constituents. Even though Eisenhower supported the CRSP, he could not get

all his fellow Republicans on board. They had been elected in 1952 on the platform of reducing government spending, and their constituents were against large spending projects, such as the CRSP. On a whole, the Republican party

remained against the project.

With the President's approval the debate was now left up to Congress to settle once and for all. In the Senate, the powerful influence of the Western states seemed to make it an easy pass, but several well-known Senators spoke

out against it, including John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey. In April of 1954, the CRSP passed the House subcommittee on Irrigation and Reclamation. This came as no surprise, because it too was dominated by Western states. The

full committee on Interior and Insular Affairs did not have a chance to vote on the CRSP until May. The debate now entered its final phase and the delay in voting gave the conservationists another great opportunity. In the spring

of 1954 they went on the offensive.

Return to Top

The publicity campaign - part 2

During the long political debate, conservationists took advantage of the delay to continue their public campaign. By the time this second committee got the chance to vote on the matter, thousands of letters had poured into

Congressional offices from people opposed to the Echo Park dam and thousands more from farmers and other opponents. The public campaign was in full swing and turned out to be a vital component of their eventual success.

One of the major avenues for spreading the word on saving Dinosaur was the print media. Numerous articles were published in conservation journals such as Living Wilderness, the National Parks Magazine, the Sierra Club Bulletin,

and Planting and Civic Comment. Articles also appeared in prominent mainstream magazines like National Geographic, which published an article about floating the Green and Yampa rivers, and in New Republic and Harper's Magazine.

Even Eleanor Roosevelt wrote against the dam in her syndicated column. Many newspapers around the country wrote in support of the campaign to save Dinosaur. John Oakes of the New York Times alone published more than 20 articles

on the subject. The conservationists also found strong support amongst editorialists from major papers around the country such as the San Francisco Chronicle, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and the Christian Science Monitor.

And thru it all, the conservationists made sure the debate remained in the public eye with regular press releases.

The Sierra Club continued to circulate its film "Wilderness River Trail" around the country, often playing it for packed audiences. David Brower produced another film entitled "Two Yosemites" that compared

the Echo Park dam to the unsuccessful attempt to save the Hetch Hetchy Valley. It was aimed mostly at Congress and showed that a reservoir did not necessarily add to the beauty of a park. The Hetch Hetchy reservoir's fluctuating

levels left ugly mudflats in many places. Brower proclaimed the film a success in the halls of Congress, and he meant that literally. On several occasions he and Howard Zahniser had set up their projector in the actual hallways

of the Capital and played their films for anyone that happened to wander by. They also handed out free copies of the newly published book "This is Dinosaur" by Alfred A. Knopf. The book, which was promoted to the general

public, as well as to Congress, was the fist of its kind. It was a book created for the specific purpose of educating the public about a wilderness location for the purpose of preserving it. The book contained essays by prominent

writers involved in the campaign, as well as beautiful, large color pictures of the park and the rivers that flowed through it.

During this final stage of the campaign to save Dinosaur, the conservationists were more organized than ever. A Supreme Court ruling in 1954 forced the many conservation groups to officially form a united lobbying group in order

to protect their individual organizations' tax exemption status. They formed the Trustees for Conservation. The lobby brought all the conservation groups into a unified organization that worked against the Echo Park dam and took

the reins in the fight for its remainder. This focused group kept the protection of the NPS and its lands as its major goal. They remained against the Echo park project, but not against the CRSP as a whole. It is for this reason

that they would not protest the eventual construction of a dam in Glen Canyon.

To the dismay of the dam's proponents, the once little known Dinosaur National Monument quickly became a nationally known symbol of the wilderness and pristine spaces that the NPS had to offer. The public's view of the National

Parks themselves was shifting from simply places for recreation, to venues for the conservation of the wilderness that was all but gone from many parts of the country. The conservationists had successfully brought DNM to the public's

attention. In 1954, the park had over 71 thousand visitors, up threefold from the previous year. Bus Hatch's river business thrived and he became a pioneer in the whitewater industry. Bus himself had some hardships in his hometown

of Vernal, UT where most of the locals were still ardent supporters of the dam and associated Bus with the conservationists he often guided down the river. Bus never directly spoke out against the dam, but the town's perceptions

led them to boycott a gas station that he booked trips from. Eventually the gas station's owner was forced to ask him to set up his booking office elsewhere. His business continued to build despite the setbacks as demand for his

trips grew each year. "Save Dinosaur" had become a national rallying cry. There seemed to be no stopping the public's growing support for the cause. Larger and more politically powerful groups, such as the Garden Club

of America, the General Federation of Women's Clubs and the National Wildlife Federation all threw their political might and letter writing abilities behind the conservationists. The publicity campaign to save DNM was a huge

success.

Return to Top

Victory

The CRSP was a major agenda item for the Congressional session that began in January of 1955. As with years past, the bill was expected to pass easily thru the Senate, but opposition grew steadily in the House. The main reasons

for concern in the House over the CRSP's passage were the Echo Park dam controversy, the growing expense of hydropower, the project's questionable cost accounting and the additional agricultural surplus that might come as a result

of the dams potential to provide a huge new area with a reliable source of water for irrigation. On April 20, 1955, the Senate officially passed the bill for the CRSP and failed to approve an amendment that would remove the Echo

Park dam. It was up to the House to save Dinosaur.

Since the Senate had failed to remove the Echo Park dam from the CRSP, the conservationists had no choice but to attack the project as a whole. They joined other groups that were opposed to the CRSP for various reasons. This

move pleased both Brower and DeVoto, who had been opposed to the CRSP since the evaporation debate, but worried other members of the coalition who remained concerned about taking such a radical stance. The Trustees made sure it

was known they would give up their opposition to the CRSP if the Echo Park dam was simply removed. This put them in the position of being one of the easiest factions allied against the CRSP to placate.

The fight to save Dinosaur came to a head in the summer of 1955. The public campaign to save it was huge. Never before had any single conservation issue been given such national publicity. Proponents of the dam began to realize

the true power the conservationists had gathered in the House. They worried that the CRSP as a whole might fail to pass the House as long as the Echo Park dam remained a part of it. On June 28, 1955, the members of the Interior

Committee, by a vote of 20 to 6, took the Echo Park dam out of the CRSP. But the conservationists did not rest. The fight was still not completely over. Neither the Senate nor the Bureau of Reclamation had agreed to delete the

Echo Park dam from the CRSP. Many House members were also skeptical of the prospect that the dam would be reinserted into the CRSP once it again went to committee. They decided to postpone a final vote on the CRSP for yet another

year and passed it off to the next session of Congress.

In late 1955, Senators from the upper basin states, who had for so long claimed that Echo Park was an essential part of the CRSP, gave in. They did not change their minds about the need for an Echo Park dam, but they did

acknowledge the political reality that the CRSP was unlikely to pass in 1956 as long as the same coalition opposed it. The conservationists were the only element of the opposition that they had the power to satisfy. In November

of 1955, the Echo Park dam was officially dropped, once and for all, from the CRSP. Secretary McKay announced its official deletion on November 29.

After six years, the conservationists had won. Not only did they manage to save Echo Park, they got wording included in the final version of the CRSP that guaranteed no NPS lands would be affected by the project. Their success

in obtaining such wording was an important legacy for the wilderness movement. With the inclusion of the provisos concerning no impact of NPS land, the conservationists officially withdrew their opposition to the CRSP in January

of 1956. Many of the conservationists would later regret not fighting Glen Canyon dam, Brower chief among them. He even tried to convince the Sierra Club board to continue to fight the CRSP, but they disagreed and beautiful

Glen Canyon was sacrificed in order to gain protection for the NPS lands as a whole. Other groups continued to fight the CRSP. California water interests took over the fight, but without the conservationists their impact and

influence was greatly diminished. The CRSP passed both houses of Congress in March of 1956 and Eisenhower signed the bill into law on April 11, 1956. The fight to save Dinosaur National Monument was officially over, and the

many conservation groups that had come together to fight it had won a major victory on the behalf of the National Park Service and the nascent American environmental movement.

We are all lucky that this dedicated group of people came together to fight the dam at Echo Park and saved Dinosaur. They not only pioneered and kick-started the American environmental movement, but they saved a truly beautiful

and wonderful part of our country and ensured that all National Parks are now safe from development. I am lucky enough to have floated the same canyons that Bus Hatch pioneered so many years ago and inspired the conservationist

coalition to take action. Next time I find myself floating past the proposed dam site, I'll be sure to give an extra tip of my hat to the fine folks that fought to save Dinosaur and be reminded that thru cooperation, dedication

and with a little luck, seemingly impossible odds can be overcome and our wild places can be protected.

Return to Top

---------------------------------------------------